Wilson Disease

Wilson’s disease is a condition where too much copper builds up in the body. It is a rare inherited disorder that affects about 1 in 30,000 people. It is named after Dr Samuel Wilson who first described the disorder in 1912.

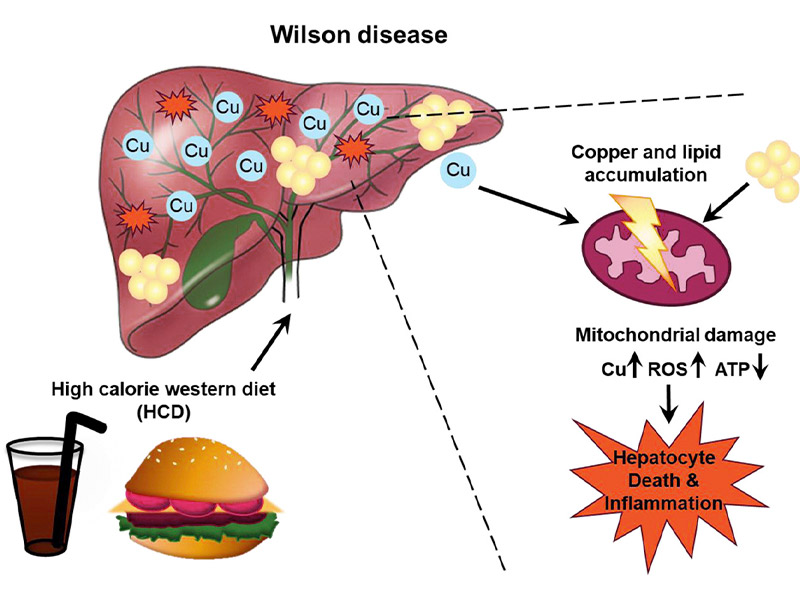

If you inherit the genetic fault in Wilson’s disease, your body is not able to get rid of copper. Copper is a trace metal which is in many foods. You need tiny amounts of copper to remain healthy. Normally, the body gets rid of any excess copper. People with Wilson’s disease cannot get rid of excess copper and so it builds up in the body, mainly in the liver, the brain, the layer at the front of the eye (called the cornea) and the kidneys.

Too much copper in the liver cells (the hepatocytes) is harmful and leads to liver damage. Damage to brain tissue mainly occurs in an area called the lenticular nucleus. Hence, Wilson’s disease is sometimes also called hepatolenticular degeneration.

What are the Symptoms?

Wilson’s disease symptoms usually start in childhood or adolescence, but have been reported in individuals who were greater than 60 years of age. One characteristic sign of Wilson disease is the Kayser-Fleischer ring – a rusty brown ring around the cornea of the eye that can be seen only through an eye exam. It is not associated with any visual problems. Other symptoms vary, depending on whether the damage occurs in the liver, blood, central nervous system, urinary system, or musculoskeletal system. These include:

Symptoms of excess copper in the liver, such as:

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

- Swelling or pain in the abdomen

- Bleeding tendency

- Vomiting blood

- Fatigue

Psychiatric symptoms of excess copper in the brain, such as:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Mood swings

- Aggressive or other inappropriate behaviors

Physical symptoms of excess copper in the brain, such as:

- Difficulty speaking and swallowing

Tremors - Rigid muscles

- Problems with balance and walking

What are the Causes?

Wilson’s disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, which means that to develop the disease you must inherit one copy of the defective gene from each parent. If you receive only one abnormal gene, you won’t become ill yourself, but you’re a carrier and can pass the gene to your children.

How is it Diagnosed?

If Wilson’s disease is suspected, it can be diagnosed by various tests:

- A blood test to measure caeruloplasmin. This is a protein that binds copper in the bloodstream. The level is low in nearly all people with Wilson’s disease.

- Other blood tests may also be performed. These may be done to measure your copper levels and to test your kidney and liver function.

- A urine test to measure the amount of copper in the urine. This is usually tested on all the urine you produce over a 24-hour period. The amount is typically higher than normal.

- An examination of the layer at the front of the eye (called the cornea) by an optician (optometrist) or an eye specialist may show the Kayser-Fleischer rings if they have developed. (They are not present in all cases.)

- A small sample (biopsy) of the liver may be taken to look at under the microscope. This can show the excess copper in the liver and the extent of any scarring of the liver (cirrhosis). See the separate leaflet called Liver Biopsy for more details.

- Your specialist may also request other tests – for example, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of your brain and your kidneys.

If Wilson’s disease is confirmed then your brothers and sisters should be checked to see if they have the condition. Brothers and sisters of a person with Wilson’s disease have a 1 in 4 chance of also having the condition.

What are the Risk Factor?

You can be at increased risk of Wilson’s disease if your parents or siblings have the condition. Ask your doctor whether you should undergo genetic testing to find out if you have Wilson’s disease. Diagnosing the condition as early as possible dramatically increases the chances of successful treatment.

Untreated, Wilson’s disease can be fatal. Serious complications include:

- Scarring of the liver (cirrhosis): As liver cells try to make repairs to damage done by excess copper, scar tissue forms in the liver, making it more difficult for the liver to function.

- Liver failure: This can occur suddenly (acute liver failure), or it can develop slowly over years. A liver transplant might be a treatment option.

- Persistent neurological problems: Tremors, involuntary muscle movements, clumsy gait and speech difficulties usually improve with treatment for Wilson’s disease. However, some people have persistent neurological difficulty despite treatment.

- Kidney problems: Wilson’s disease can damage the kidneys, leading to problems such as kidney stones and an abnormal number of amino acids excreted in the urine.

- Psychological problems. These might include personality changes, depression, irritability, bipolar disorder or psychosis.

- Blood problems: These might include destruction of red blood cells (hemolysis) leading to anemia and jaundice.

How is it Treated?

Your doctor might recommend medications called chelating agents, which bind copper and then prompt your organs to release the copper into your bloodstream. The copper is then filtered by your kidneys and released into your urine.

Treatment then focuses on preventing copper from building up again. For severe liver damage, a liver transplant might be necessary.

Medications: If you take medications for Wilson’s disease, treatment is lifelong.

Surgery: If your liver damage is severe, you might need a liver transplant. During a liver transplant, a surgeon removes your diseased liver and replaces it with a healthy liver from a donor.